eDiscovery Daily Blog

eDiscovery Searching: For Defensible Searching, Be a "STARR"

Defensible searching has become a priority in eDiscovery as parties in several cases have experienced significant consequences (including sanctions) for not implementing a defensible search strategy in responding to discovery requests.

Probably the most famous case where search approach has been an issue was Victor Stanley, Inc. v. Creative Pipe , Inc., 250 F.R.D. 251 (D. Md. 2008), where Judge Paul Grimm noted that “only prudent way to test the reliability of the keyword search is to perform some appropriate sampling of the documents” and found that privilege on 165 inadvertently produced documents was waived, in part, because of the inadequacy of the search approach.

A defensible search strategy is part using an effective tool (with advanced search capabilities such as “fuzzy”, wildcard, synonym and proximity searching) and part using an effective approach to test and verify search results.

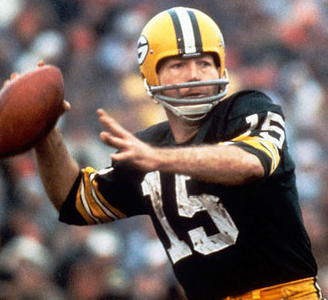

I have an acronym that I use to reflect the defensible search process. I call it “STARR” – as in “STAR” with an extra “R” or Green Bay Packer football legend Bart Starr (sorry, Bears fans!). For each search that you need to conduct, here’s how it goes:

- Search: Construct the best search you can to maximize recall and precision for the desired result. An effective tool gives you more options for constructing a more effective search, which should help in maximizing recall and precision. For example, as noted on this blog a few days ago, a proximity search can, under the right circumstances, provide a more precise search result without sacrificing recall.

- Test: Once you’ve conducted the search, it’s important to test two datasets to determine the effectiveness of the search:

- Result Set: Test the result set by randomly selecting an appropriate sample percentage of the files and reviewing those to determine their responsiveness to the intent of the search. The appropriate percentage of files to be reviewed depends on the size of the result set – the smaller the set, the higher percentage of it that should be reviewed.

- Files Not Retrieved: While testing the result set is important, it is also important to randomly select an appropriate sample percentage of the files that were not retrieved in the search and review those as well to see if any responsive hits are identified as missed by the search.

- Analyze: Analyze the results of the random sample testing of both the result set and also the files not retrieved to determine how effective the search was in retrieving mostly responsive files and whether any responsive files were identified as missed by the search performed.

- Revise: If the search retrieved a low percentage of responsive files and retrieved a high percentage of non-responsive files, then precision of the search may need to be improved. If the files not retrieved contained any responsive files, then recall of the search may need to be improved. Evaluate the results and see what, if any, revisions can be made to the search to improve precision and/or recall.

- Repeat: Once you’ve identified revisions you can make to your search, repeat the process. Search, Test, Analyze and (if necessary) Revise the search again until the precision and recall of the search is maximized to the extent possible.

While you can’t guarantee that you will retrieve all of the responsive files or eliminate all of the non-responsive ones, a defensible approach to get as close as you can to that goal will minimize the number of files for review, potentially saving considerable costs and making you a “STARR” in the courtroom when defending your search approach.

So, what do you think? Are you a “STARR” when it comes to defensible searching? Please share any comments you might have or if you’d like to know more about a particular topic.