Assessing the Proportionality of Modern Data Types

The Costs of eDiscovery

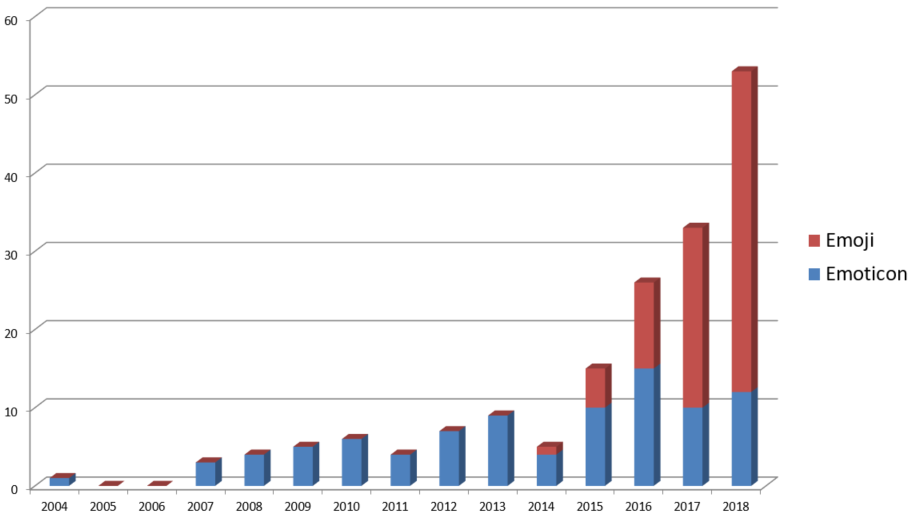

As time passes, the definition of electronically stored information (ESI) must expand to accommodate emerging data types. As discussed in our recent article, (Don’t Get Spooked by Communication Applications!), these changes can be intimidating and uncomfortable for some legal teams. Since modern data types are unavoidable in eDiscovery, litigators must adapt and address any subsequent challenges. Financing the production of newer ESI types is a looming concern for many firms. From a financial perspective, each gigabyte of reviewed data costs about $18,000. [1] Meanwhile, 300 million photos are posted to social media every day, and 16 million texts are sent every minute. [2] In addition to paying for production, responding parties must have adequate access and resources to manage the information. If responding parties cannot juggle these duties, they should speak with the judge and requesting party about the proportionality of the evidence.

Proportionality and Amendments to Rule 26(b)(1)

Before requesting the production of digital evidence in a legal trial, the proportionality of said evidence must be evaluated. In other words, the costs and benefits of production must be weighed. Proportionality is far from a new concept in eDiscovery. Most of its factors and considerations were first added to Rule 26(b)(1) of the FRCP in 1983. On December 1, 2015, the rule was amended slightly to require that the scope of discovery be “proportional to the needs of the case.” [3] Six factors should be considered when evaluating the proportionality of ESI:

- The importance of the issues at stake in the action – This guideline measures the importance of the non-monetary losses or gains that a party might acquire due to a case (i.e. time, resources).

- The amount of controversy – This guideline focuses on the money that a party may gain or lose.

- The parties’ access to relevant information – The need for a formal discovery is determined based on a party’s access (or lack thereof) to relevant information.

- The parties’ resources – A party’s technological, administrative, and human resources are assessed to determine if they are capable of handling the discovery process.

- The importance of the discovery in resolving the issues – This guideline relates to the discovery’s importance in resolving the case.

- Whether the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit – The burdens and benefits of discovery are compared. There is no fixed ratio to determine the proportionality. [4]

Proportionality Best Practices

- Parties should engage in discovery planning early on. Discussions on the relevance and proportionality of the request should be held as soon as possible.

- Prior to Rule 26(f), meet in person (or over the phone) to develop a discovery management plan.

- Ask the judge to hold Rule 16(b) case-management conferences.

- If you anticipate proportionality disputes or the production of voluminous data, start the discovery process by producing the most accessible and relevant information . [4]

[1] Patrick E. Gaas and Tiffany Harrod, “How to Proactively Control E-discovery Costs,” Tech Brief, AGC of America.

[2] Bernard Marr, “How Much Data Do We Create Every Day? The Mind-blowing Stats Everyone Should Read,” Forbes, May 21, 2018.

[3] “Rule 26. Duty to Disclose; General Provisions Governing Discovery,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School,

[4] Bolch Judicial Institute, “Guidelines and Best Practices for Implementing the 2015 Discovery Amendments Concerning Proportionality,” Third Edition, 2021.