Would eDiscovery Have Identified the Correct Murderer in “Making a Murderer”?: eDiscovery Best Practices

The recently released Netflix documentary Making a Murderer has made a huge splash with hundreds of thousands of viewers (including me) having watched the 10 part documentary that was released last month. Debate has raged over whether Steven Avery and his nephew, Brendan Dassey, were wrongly convicted of murdering photographer Teresa Halbach. Interestingly enough, some possibly deleted electronic evidence might have helped answer that question.

In an article on ACEDS (Making a Murderer: The Missing Computer Forensics Evidence), the author (Jason Krause) discusses the fact that there voicemail messages on Halbach’s phone that allegedly disappeared. Krause discusses the information presented in the documentary regarding the voicemail messages, as follows:

“Halbach’s family reported her missing in early November 2005 after finding that they called her cellphone and received a recorded message saying the voicemail box was full. According to her family, it was not like Halbach to not check her messages and decided to alert the police that she may be missing.

However, Teresa’s ex-boyfriend Ryan Hillegas testified that he listened to her voicemails after breaking into her inbox in an attempt to learn more about where she had last been. “I had a feeling that I might know her voicemail password,” he said in the episode, in order to explain how he retrieved the voice mails. However, he claimed that he did not delete any messages. [It was actually her brother, Mike Halbach, who stated that he had listened to her messages, though Hillegas indicated that he had accessed her phone records after also guessing Teresa’s password.]

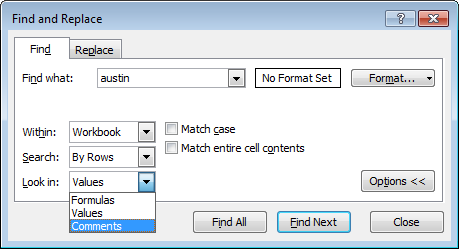

However, the only expert called to testify in this matter was Tony Zimmerman, a network engineer with Cingular Wireless, Halbach’s phone provider. He testified that calls and messages that the phone had received, should not have filled up the full capacity of the mailbox. Avery’s lawyers speculated that someone had erased potentially incriminating messages before Halbach was reported missing.

Unfortunately, Zimmerman was not a trained computer forensic examiner and his testimony did not reflect that any investigation more rigorous than looking at Halbach’s call log.”

Krause’s article quotes David Greetham, Vice President of eDiscovery Operations with Ricoh Americas Corporation, who recalled that “as long ago as 2001 we were recovering deleted text messages from a defendant accused of drug dealing”, but also noted that “law enforcement often has budget restrictions on training and resources”, which could limit the ability to investigate such leads (back in 2005 especially). Of course, if you’re like many viewers who believe that the Manitowoc sheriff’s department had a vested interest in seeing Avery arrested for the crime (particularly since he had filed a $36 million lawsuit against the department for his wrongful conviction in a 1985 rape case), you may think that they were less than highly motivated to pursue this lead.

Regardless of whether or not you believe that Avery and Dassey were wrongfully convicted (and, apparently, several instances of incriminating evidence regarding their potential involvement were not covered in the documentary), the question remains: Were there voicemail messages that were deleted and could they have affected the outcome of the case? If there had been a trained computer forensic examiner on the case back then, perhaps there would have been some additional information uncovered that either pointed to a different suspect or added to the evidence that implicated Avery. Over ten years have passed since the murder took place, so we will probably never know.

So, what do you think? Do you find the lack of investigation of the voice mail messages disconcerting? Please share any comments you might have or if you’d like to know more about a particular topic.

Disclaimer: The views represented herein are exclusively the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views held by CloudNine. eDiscovery Daily is made available by CloudNine solely for educational purposes to provide general information about general eDiscovery principles and not to provide specific legal advice applicable to any particular circumstance. eDiscovery Daily should not be used as a substitute for competent legal advice from a lawyer you have retained and who has agreed to represent you.