Court Rules that Unilateral Predictive Coding is Not Progressive – eDiscovery Case Law

In Progressive Cas. Ins. Co. v. Delaney, No. 2:11-cv-00678-LRH-PAL (D. Nev. May 19, 2014), Nevada Magistrate Judge Peggy A. Leen determined that the plaintiff’s unannounced shift from the agreed upon discovery methodology, to a predictive coding methodology for privilege review was not cooperative. Therefore, the plaintiff was ordered to produce documents that met agreed-upon search terms without conducting a privilege review first.

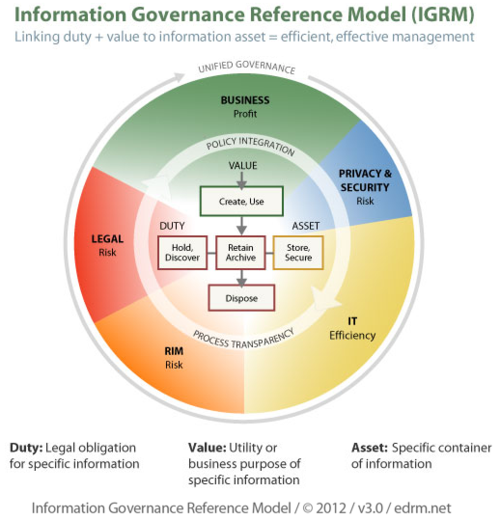

This declaratory relief action had been plagued by delays in discovery production, which led to the defendants filing a Motion to Compel the plaintiffs to produce discovery in a timely fashion. Following a hearing, both sides were ordered to meet and confer, and hold meaningful discussions about resolving outstanding ESI issues pursuant to discovery. The plaintiff contended that the defendant’s discovery requests, as standing, would require them to produce approximately 1.8 million documents, which would be unduly burdensome. Both parties agreed to search terms that would reduce the number of potentially responsive documents to around 565,000, which the plaintiff would manually review for privileged documents before producing discovery to the defendant.

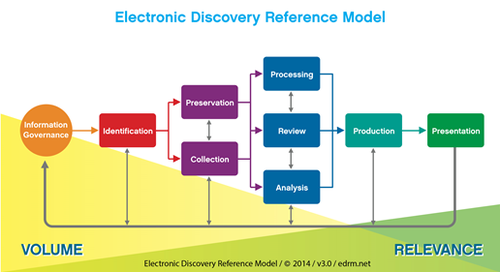

Shortly thereafter, the plaintiff determined that manual review would be too expensive and time-consuming, and therefore after consulting with a “nationally-recognized authority on eDiscovery,” elected to apply predictive coding to the identified 565,000 documents. Plaintiff selected a software program that they began using to identify relevant documents with the intention of applying a further predictive coding layer in order to determine which documents were “more likely privileged” and which were “less likely privileged.”

However, the plaintiff did not consult with either the court or the requesting party regarding their intentions to change review methodology. As a result, the defendant objected to the use of predictive coding in this case for several reasons, including the plaintiff’s lack of transparency surrounding its predictive coding methodology and its failure to cooperate, as well as the plaintiff’s failure to adhere to the best practices for the chosen software program which were recommended to them by the authority they chose. Finally, the defendants cited a likelihood of satellite disputes revolving around discovery, should the plaintiff proceed with the current predictive coding, which would further delay production discovery that had already been “stalled for many months.”

The defendant requested that either the plaintiff be required to proceed with predictive coding according to the defendant’s suggested protocol, which would include applying the predictive methodology to all of the originally collected 1.8 million documents, or that the plaintiff produce the non-privileged keyword hits without any review, but allowing them to be subject to a clawback order—which was a second option included in the originally stipulated ESI protocol that both parties had agreed to. Although this option would shift the burden of discovery to the defendant, it was noted that the defendant was “committed to devot[ing] the resources required to review the documents as expeditiously as possible” in order to allow discovery to move forward.

Judge Leen acknowledged potential support for the general methodology of predictive coding in eDiscovery, and stated that a “transparent mutually agreed upon” protocol for such a method would likely have been approved. However, Judge Leen took issue that the plaintiff had refused to “engage in the type of cooperation and transparency that its own eDiscovery consultant has so comprehensibly and persuasively explained is needed for a predictive coding protocol to be accepted by the court or opposing counsel” and instead had “elected and then abandoned the second option—to manually review and produce responsive ESI documents. It abandoned the option it selected unilaterally, without the [defendant’s] acquiescence or the court’s approval and modification of the parties’ stipulated ESI protocol.”

Therefore, Judge Leen elected to enforce the second option described in the agreed-upon ESI protocol, and required the plaintiff to produce all 565,000 documents that matched the stipulated search terms without review, with a clawback option in place for privileged documents as well as permission to apply privilege filters to the documents at issue, and withhold those documents that returned as “most likely privileged.”

So, what do you think? Should parties need to obtain approval regarding the review methodology that they plan to use? Please share any comments you might have or if you’d like to know more about a particular topic.

Disclaimer: The views represented herein are exclusively the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views held by CloudNine Discovery. eDiscoveryDaily is made available by CloudNine Discovery solely for educational purposes to provide general information about general eDiscovery principles and not to provide specific legal advice applicable to any particular circumstance. eDiscoveryDaily should not be used as a substitute for competent legal advice from a lawyer you have retained and who has agreed to represent you.