This Guy Says that Computers Could Eventually Replace Lawyers – In the Courtroom: eDiscovery Trends

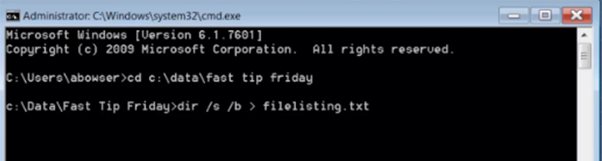

Over four years ago, we covered an article in The New York Times that discussed how the use of artificial intelligence could lead to replacing “armies of expensive lawyers” during the eDiscovery process. Now, a new article in The Wall Street Journal online goes a step further, speculating that “computers will eventually pass the legal bar exam and defendants will be given the right to be represented by a computational attorney if they so wish”.

What Big Data Means for the Legal System, written by Robert Plant (not the Led Zeppelin singer, but a professor at the University of Miami, as well as an author and blogger for Harvard Business Review & WSJ Leadership Expert) discusses how artificial intelligence researchers have used the legal domain as an exploratory space to test theories for decades, but with limited success. The advent of big data has changed that, enabling us to analyze not only text but many other data types such as pictures, email, video and voice. As Plant notes, this capability “allows lawyers to look for patterns and correlations across vast data sets previously inaccessible.”

Plant uses analysis of judges’ behavior in cases as an example, suggesting the ability to obtain answers to questions like: “How does the Judge rule on certain types of cases can be studied by date and time? Does the judge dismiss cases for a consistent pattern of reasoning? How do holidays affect decisions? Do they sentence harder at different times of the day?”

Because of big data analytics, Plant predicts that “[m]any of the routine tasks now performed by entry-level lawyers or paralegals will increasingly be undertaken by analytics; case and trial strategies will be developed by legal informatics as will increasingly jury-selection strategies.” As a result, Plant takes the concept to a somewhat controversial conclusion, as follows:

“It is clear that with advances in machine learning, computers will eventually pass the legal bar exam and defendants will be given the right to be represented by a computational attorney if they so wish and thus court rooms could see a truly new form of human computer interaction in which the computer answers the question ‘does the client have a case?’”

Must he “ramble on”? Computers replace lawyers?!? In the courtroom?!? He sure isn’t showing the legal profession a “whole lotta love”, is he? (sorry, I couldn’t resist)

Clearly, we’ve seen the application of artificial intelligence result in significant benefits during the eDiscovery process, with several cases over the past few years endorsing technology assisted review (including this latest case just last month) as well as initiatives to apply technology to information governance (such as the Information Governance Initiative launched last year). Is it that far of a stretch to apply technology to decision making in the courtroom too? Or is the author simply “dazed and confused”? (ok, I really will stop now)

So, what do you think? Will clients someday be represented by computers in the courtroom? Please share any comments you might have or if you’d like to know more about a particular topic.

Clipart from Clipartheaven.com

Disclaimer: The views represented herein are exclusively the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views held by CloudNine. eDiscovery Daily is made available by CloudNine solely for educational purposes to provide general information about general eDiscovery principles and not to provide specific legal advice applicable to any particular circumstance. eDiscovery Daily should not be used as a substitute for competent legal advice from a lawyer you have retained and who has agreed to represent you.