eDiscovery History: Zubulake’s e-Discovery

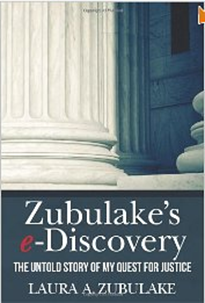

In the 22 months since this blog began, we have published 133 posts related to eDiscovery case law. When discussing the various case opinions that involve decisions regarding to eDiscovery, it’s easy to forget that there are real people impacted by these cases and that the story of each case goes beyond just whether they preserved, collected, reviewed and produced electronically stored information (ESI) correctly. A new book, by the plaintiff in the most famous eDiscovery case ever, provides the “backstory” that goes beyond the precedent-setting opinions of the case, detailing her experiences through the events leading up to the case, as well as over three years of litigation.

Laura A. Zubulake, the plaintiff in the Zubulake vs. UBS Warburg case, has written a new book: Zubulake's e-Discovery: The Untold Story of my Quest for Justice. It is the story of the Zubulake case – which resulted in one of the largest jury awards in the US for a single plaintiff in an employment discrimination case – as told by the author, in her words. As Zubulake notes in the Preface, the book “is written from the plaintiff’s perspective – my perspective. I am a businessperson, not an attorney. The version of events and opinions expressed are portrayed by me from facts and circumstances as I perceived them.” It’s a “classic David versus Goliath story” describing her multi-year struggle against her former employer – a multi-national financial giant.

Zubulake begins the story by developing an understanding of the Wall Street setting of her employer within which she worked for over twenty years and the growing importance of email in communications within that work environment. It continues through a timeline of the allegations and the evidence that supported those allegations leading up to her filing of a discrimination claim with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and her subsequent dismissal from the firm. This Allegations & Evidence chapter is particularly enlightening to those who may be familiar with the landmark opinions but not the underlying evidence and how that evidence to prove her case came together through the various productions (including the court-ordered productions from backup tapes). The story continues through the filing of the case and the beginning of the discovery process and proceeds through the events leading up to each of the landmark opinions (with a separate chapter devoted each to Zubulake I, III, IV and V), then subsequently through trial, the jury verdict and the final resolution of the case.

Throughout the book, Zubulake relays her experiences, successes, mistakes, thought processes and feelings during the events and the difficulties and isolation of being an individual plaintiff in a three-year litigation process. She also weighs in on the significance of each of the opinions, including one ruling by Judge Shira Scheindlin that may not have had as much impact on the outcome as you might think. For those familiar with the opinions, the book provides the “backstory” that puts the opinions into perspective; for those not familiar with them, it’s a comprehensive account of an individual who fought for her rights against a large corporation and won. Everybody loves a good “David versus Goliath story”, right?

The book is available at Amazon and also at CreateSpace. Look for my interview with Laura regarding the book in this blog next week.

So, what do you think? Are you familiar with the Zubulake opinions? Have you read the book? Please share any comments you might have or if you’d like to know more about a particular topic.

Disclaimer: The views represented herein are exclusively the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views held by CloudNine Discovery. eDiscoveryDaily is made available by CloudNine Discovery solely for educational purposes to provide general information about general eDiscovery principles and not to provide specific legal advice applicable to any particular circumstance. eDiscoveryDaily should not be used as a substitute for competent legal advice from a lawyer you have retained and who has agreed to represent you.