Word’s Stupid “Smart Quotes” – Best of eDiscovery Best Practices

Even those of us at eDiscoveryDaily have to take an occasional vacation day; however, instead of “going dark” for today, we thought we would republish a post from the early days of the blog (when we didn’t have many readers yet). So, chances are, you haven’t seen this post yet! Enjoy!

I have run into this issue more times than I can count.

A client sends me a list of search terms that they want to use to cull a set of data for review in a Microsoft® Word document. I copy the terms into the search tool and then, all hell breaks loose!! Either:

The search indicates there is a syntax error

OR

The search returns some obviously odd results

And, then, I remember…

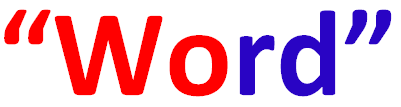

It’s those stupid Word “smart quotes”. Starting with Office 2003, Microsoft Word, by default, automatically changes straight quotation marks ( ‘ or ” ) to curly quotes as you type. This is fine for display of a document in Word, but when you copy that text to a format that doesn’t support the smart quotes (such as HTML or a plain text editor), the quotes will show up as garbage characters because they are not supported ASCII characters. So:

“smart quotes”

will look like this…

âsmart quotesâ

As you can imagine, that doesn’t look so “smart” when you feed it into a search tool and you get odd results (if the search even runs). So, you’ll need to address those to make sure that the quotes are handled correctly when searching for phrases with your search tool.

To disable the automatic changing of quotes to Microsoft Word smart quotes: Click the Microsoft Office icon button at the top left of Word, and then click the Word Options button to open options for Word. Click Proofing along the side of the pop-up window, then click AutoCorrect Options. Click the AutoFormat tab and uncheck the Replace “Smart Quotes” with “Smart Quotes” check box. Then, click OK.

Often, however, the file you’ve received already has smart quotes in it. If you’re going to use the terms in that file, you’ll need to copy them to a text editor first – (e.g., Notepad or Wordpad – if Wordpad is in plain text document mode) should be fine. Highlight the beginning quote and copy it to the clipboard (Ctrl+C), then Ctrl+H to open up the Find and Replace dialog, put your cursor in the Find box and press Ctrl+V to paste it in. Type the “ character on the keyboard into the Replace box, then press Replace All to replace all beginning smart quotes with straight ones. Repeat the process for the ending smart quotes. You’ll also have to do this if you have any single quotes, double-hyphens, fraction characters (e.g., Word converts “1/2” to “½”) that impact your terms.

So, what do you think? Have you ever run into issues with Word smart quotes or other auto formatting options? Please share any comments you might have or if you’d like to know more about a particular topic.

Disclaimer: The views represented herein are exclusively the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views held by CloudNine Discovery. eDiscoveryDaily is made available by CloudNine Discovery solely for educational purposes to provide general information about general eDiscovery principles and not to provide specific legal advice applicable to any particular circumstance. eDiscoveryDaily should not be used as a substitute for competent legal advice from a lawyer you have retained and who has agreed to represent you.