TIFFs, PDFs, or Neither: How to Select the Best Production Format

Through Rule 34(b) of the FRCP, the requesting party may select the form(s) of production based on the needs of the case. Though this flexibility better serves the client, it also begs a few important questions: What is the best form of production? Is there one right answer? Since there are multiple types of ESI, it’s hard to definitively say that one format type is superior. Arguably, any form is acceptable so long as it facilitates “orderly, efficient, and cost-effective discovery.” Requesting parties may ask for ESI to be produced in native, PDF, TIFF, or paper files. Determinations typically consider the production software’s capabilities as well as the resources accessible to the responding party. [1] The purpose of this article is to weigh the advantages and disadvantages of each type so that legal teams can make informed decisions in the future.

Production Options

- Native – As the often-preferred option, native files are produced in the same format in which the ESI was created. Since native files require no conversions, they save litigants time and money. True natives also contain metadata and other information that TIFF and PDF files may lack. Litigants may also be interested in native files for their clear insights into dynamic content (such as comments and animations). TIFFs and PDFs can only process dynamic content through overlapping static images. This cluttered format is often confusing and hard to decipher. Though useful, litigants must be careful with the metadata and dynamic content because they may contain sensitive or privileged information. [2] Native files may seem like the superior choice, but they aren’t always an option. Unfortunately, some ESI types cannot be reviewed unless they are converted into a different form. Additionally, reviewers utilizing this format are unable to add labels or redactions to the individual pages.

- TIFF – TIFFs (tagged image format files) are black and white, single-paged conversions of native files. Controllable metadata fields, document-level text, and an image load file are included in this format. Though TIFFs are more expensive to produce than native files, they offer security in the fact that they cannot be manipulated. Other abilities that differentiate TIFFs include branding, numbering, and redacting information. [3] To be searchable, TIFFs must undergo Optical Character Recognition (OCR). OCR simply creates a text version of the TIFF document for searching purposes.

- PDFs – Similar to TIFFs, PDFs also produce ESI through static images. PDFs can become searchable in two ways. The reviewer may choose to simply save the file as a searchable document, or they can create an OCR to accompany the PDF. However, OCR cannot guarantee accurate search results for TIFFs or PDFs. [1] Advocates for PDFs cite the format’s universal compatibility, small file size, quick download speeds, clear imaging, and separate pages. [4]

- Paper – As the least expensive option, paper production may be used for physical documents or printing digital documents. Many litigants prefer to avoid paper productions because they don’t permit electronic review methods. All redactions and bates stamps must be completed manually. This may be okay for a case that involves a small amount of ESI. However, manually sorting and searching through thousands of documents is time-consuming and exhausting. Litigants who opt for this format also miss out on potentially relevant metadata. [3]

[1] Clinton P. Sanko and Cheryl Proctor, “The New E-Discovery Battle of the Forms,” For The Defense, 2007.

[2] “Native File,” Thomas Reuters Practical Law.

[3] Farrell Pritz P.C. “In What Format Should I Make My Production? And, Does Format Matter?” All About eDiscovery, May 30, 2019.

[4] “PDF vs. TIFF,” eDiscovery Navigator, February 13, 2007.

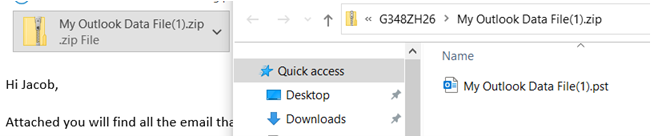

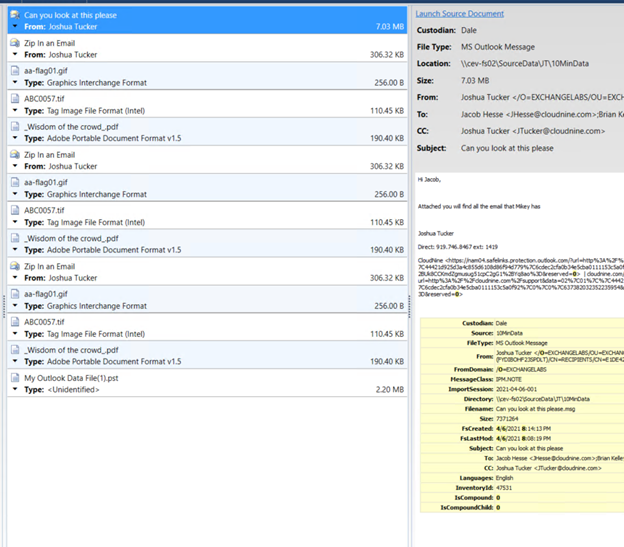

A custodian creates a PST file containing several dozen messages about a particular topic and emails it to a co-worker.

A custodian creates a PST file containing several dozen messages about a particular topic and emails it to a co-worker.