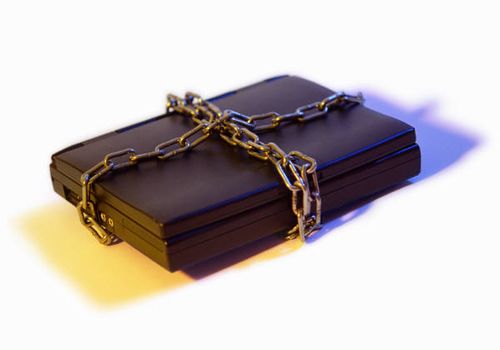

As the sources of electronic files continue to become more diverse, case law associated with those different sources has become more commonplace. One ruling in a case last month resulted in an adverse instruction against the US Government for failing to preserve text messages.

In United States v. Suarez, (D.N.J. Oct. 21, 2010), United States District Judge Jose L. Linares considered adverse inference sanctions related to the Government’s failure to preserve text messages. In this case, the F.B.I. should have retained text messages between a cooperating witness and F.B.I. agents because it was reasonably foreseeable that the text messages would be discoverable by defendants in later criminal proceedings. However, given the lack of evidence of Government bad faith in failing to impose a litigation hold on the text messages until seven months after its investigation ended, the court imposed the “least harsh” spoliation adverse inference instruction that would allow but not require the jury to infer that missing text messages were favorable to defendants.

A cooperating witness posed as a developer and, as instructed by Federal Bureau of Investigation agents, offered payments to local public officials in exchange for expediting his projects and other assistance. During the F.B.I. investigation, the witness exchanged Short Message Service electronic communications (text messages) with F.B.I. agents. In later criminal proceedings, the government notified the court that it had incorrectly stated that no text messages were missing. The court held a hearing at which F.B.I. agents and information technology specialists described F.B.I. procedures to preserve and retrieve data generated by handheld devices. Despite an F.B.I. Corporate Policy Directive on data retention and litigation hold policies, no litigation hold was in place when the cooperating witness was “texting” with agents.

In a “not-for-publication” decision, the court pointed out that the Government’s obligation under Fed. R. Crim. P. 16 to disclose information was more limited than its obligation under civil discovery rules. However, the text messages with the witness were “statements” under the Jencks Act that should have been preserved by the Government. The F.B.I. was “well-equipped” to preserve documents, and the U.S. Attorney “was aware of the importance of preserving documents relevant to the litigation and could have requested a litigation hold on the text messages from the inception of the investigation.” The request for a litigation hold was not made until seven months after the investigation ended and three months after the F.B.I. began searching its servers for missing text messages.

In determining sanctions, the court considered precedents in the civil cases of MOSAID Techs. Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., 348 F. Supp. 2d 332 (D.N.J. 2004), and Pension Comm. of the Univ. of Montreal Pension Plan v. Banc of Am. Sec., LLC, 685 F. Supp. 2d 456 (S.D.N.Y. 2010). The court concluded there was “little evidence” of Government bad faith leading to loss of the text messages. On the other hand, evidence indicated the defense was prejudiced by the loss of text messages with the cooperating witness, whose credibility was “of paramount importance.” The court thus denied defendants’ request for the “relatively severe” sanction of suppression of the witness’s testimony and all tape recordings in which he was a party. However, an adverse inference instruction was appropriate under MOSAID criteria. The text messages had been within the Government’s control and were intentionally deleted by F.B.I. agents, and the U.S. Attorneys’ Office failed to take steps to preserve the messages. The messages were relevant to claims or defenses, and it was reasonably foreseeable by the Government that the messages would later be discoverable. The court concluded that the “least harsh” spoliation adverse inference jury instruction described in Pension Committee would be issued because Government bad faith had not been shown. Such an instruction would allow but not require the jury to infer that missing text messages were favorable to defendants.

So, what do you think? Have you encountered a case where preservation of text messages was a critical component? Please share any comments you might have or if you’d like to know more about a particular topic.

Case Summary Source: Applied Discovery (free subscription required). For eDiscovery news and best practices, check out the Applied Discovery Blog here.

Disclaimer: The views represented herein are exclusively the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views held by CloudNine Discovery. eDiscoveryDaily is made available by CloudNine Discovery solely for educational purposes to provide general information about general eDiscovery principles and not to provide specific legal advice applicable to any particular circumstance. eDiscoveryDaily should not be used as a substitute for competent legal advice from a lawyer you have retained and who has agreed to represent you.