Editor’s Note: Tom O’Connor is a nationally known consultant, speaker, and writer in the field of computerized litigation support systems. He has also been a great addition to our webinar program, participating with me on several recent webinars. Tom has also written several terrific informational overview series for CloudNine, including his most recent one, DOS and DON’TS of a 30(b)(6) Witness Deposition. Now, Tom has written another terrific overview regarding mobile device collection titled Mobile Collection: It’s Not Just for iPhones Anymore that we’re happy to share on the eDiscovery Daily blog. Enjoy! – Doug

Tom’s overview is split into four parts, so we’ll cover each part separately. The first part was last Thursday, here’s the second part.

Mobile Collection and Preservation, Courtesy of Craig Ball

As I mentioned in the Introduction, Craig Ball has provided a lot of terrific information regarding preservation and collection of data from mobile devices. These are terrific resources that everyone who deals with discovery of mobile devices should be aware of. His original discussion about preservation of cell phone data was a 2017 article called Custodian-Directed Preservation of iPhone Content: Simple. Scalable. Proportional and, as the title denotes, dealt with iPhones. It proposed a wonderfully simple way to preserve iPhone data using iTunes. Although it did not preserve email, content from iTunes or iBooks, some data stored in iCloud and data from Apple Pay, Activity, Health or Keychain. Additionally, it offered several advantages in Craig’s mind to an iCloud backup, primarily that it took less time and you could choose not to encrypt the backup.

I disagreed with the last point but it’s a minor quibble and not worth discussing here because, well, all good things must come to an end and Apple last year decided to end iTunes. So Craig wrote another article entitled How Will We Back Up iPhones Without iTunes? in which he noted the good thing that ended had morphed into a better thing. As he explained, “In fact, preserving iPhones may be easier for Mac users as Apple is shifting the backup tool into the Finder app. You’ll do exactly the same thing I wrote about but Mac users with Catalina won’t even need to use iTunes to preserve mobile evidence. It’ll be built in.”

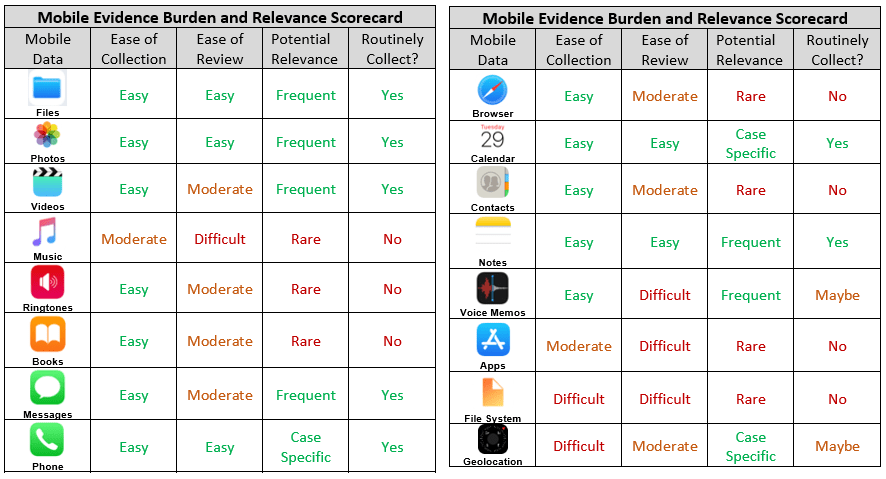

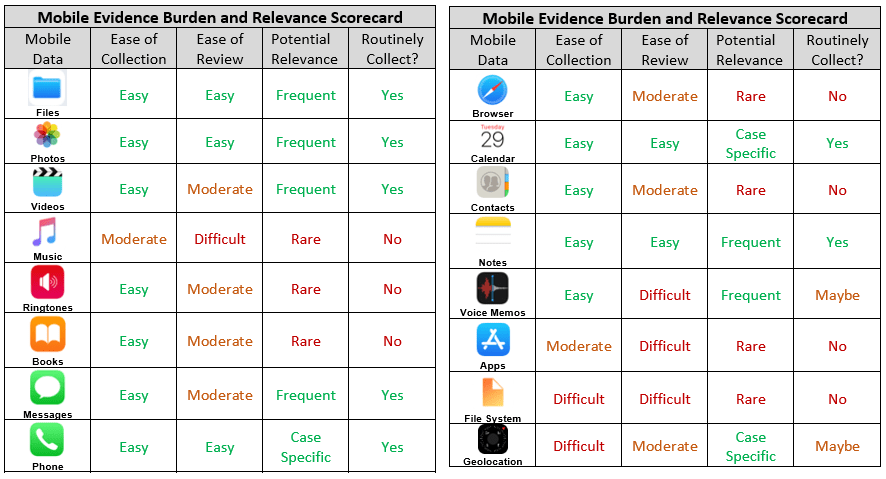

In between those two articles, Craig also wrote a piece called Mobile to the Mainstream which discussed all the various data types on a smart phone and provided a Mobile Evidence Scorecard, which rated the data types by ease of collection, ease of review, potential relevance and whether they should be part of a routine backup collection process. Everyone should have this card. Here is a representation of it, split into a front and back section.

And, last but not least, Craig compiled all of his accumulated wisdom about mobile evidence (well, iPhone mobile evidence) into a white paper called Mobile to the Mainstream: Preservation and Extraction of iOS Content for E-Discovery. I should note that the title violated one of Craig’s most often discussed issues with searching ESI. But search is also a topic for another day.

Craig finally turned to Androids last fall. Although that was actually not his first mention of the “other” OS, that came in a 2015 paper Opportunities and Obstacles: E-Discovery from Mobile Devices. But a column in this venue pointed out the most recent advances in Android collection.

Called Craig Ball is “That Guy” Who Keeps Us Up to Date on Mobile eDiscovery Trends: eDiscovery Best Practices, Doug Austin noted how Craig discussed Google’s recently expanded offering of “cheap-and-easy” online backup of Android phones, including SMS and MMS messaging, photos, video, contacts, documents, app data and more. In that discussion, Craig stated: “This is a leap forward for all obliged to place a litigation hold on the contents of Android phones — a process heretofore unreasonably expensive and insufficiently scalable for e-discovery workflows. There just weren’t good ways to facilitate defensible, custodial-directed preservation of Android phone content. Instead, you had to take phones away from users and have a technical expert image them one-by-one.”

Now as a character in the movie Independence Day once said …. “that’s not ENTIRELY correct.” Craig was referring to Google One, the recent addition intended to improve archiving capabilities. But as Google notes on their own website. “We’ve taken the standard Android backup (my emphasis added) that includes texts, contacts, and apps and we’re giving you even more.”

The new automatic phone backup also addresses photos, videos, and multimedia messages (MMS) and it can all be done from a Google One app.

But backups did exist before this. Craig himself mentions Google TakeOut, which has long allowed users of Google products, such as YouTube and Gmail, to export their data to a downloadable archive file. Started with some basic services in 2011, TakeOut expanded to include Gmail and Google Calendar in 2013. By 2016, Google had grown the service to include search history and Wallet details and since then, they have also added Google Hangouts to the Takeout service. In all cases, TakeOut does not delete user data automatically after exporting.

We’ll publish Part 3 – Google Vault and the Emphasis of Android Devices – on Wednesday.

So, what do you think? Are you having to increasingly address issues associated with mobile device discovery? As always, please share any comments you might have or if you’d like to know more about a particular topic.

Sponsor: This blog is sponsored by CloudNine, which is a data and legal discovery technology company with proven expertise in simplifying and automating the discovery of data for audits, investigations, and litigation. Used by legal and business customers worldwide including more than 50 of the top 250 Am Law firms and many of the world’s leading corporations, CloudNine’s eDiscovery automation software and services help customers gain insight and intelligence on electronic data.

Disclaimer: The views represented herein are exclusively the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views held by CloudNine. eDiscovery Daily is made available by CloudNine solely for educational purposes to provide general information about general eDiscovery principles and not to provide specific legal advice applicable to any particular circumstance. eDiscovery Daily should not be used as a substitute for competent legal advice from a lawyer you have retained and who has agreed to represent you.