eDiscovery Blog Throwback Thursdays – How things evolved, Part 2

So far in this blog series, we’ve taken a look at the ‘litigation support culture’ circa 1980, and we’ve covered how databases were built and used. We’ve come a long way since then, and in last week’s blog, we started discussing how things have evolved. In the next posts, we’ll continue discussion of things evolved, but first, if you missed the earlier posts in this series, they can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.

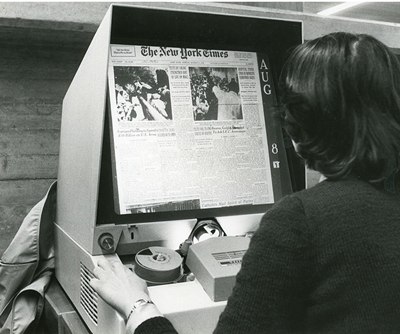

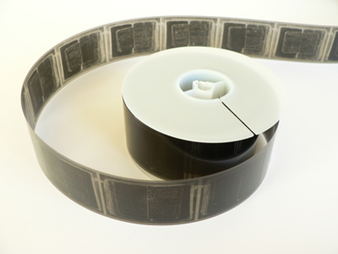

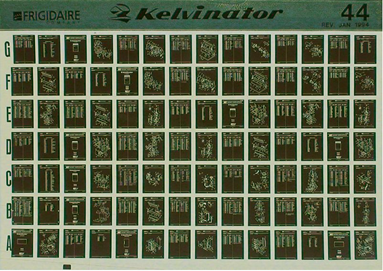

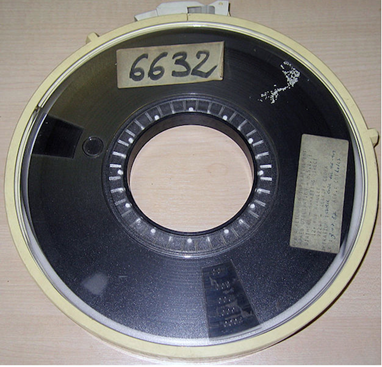

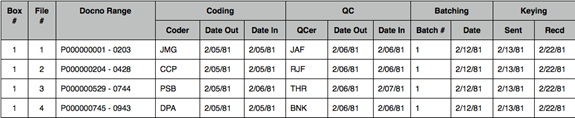

Last week, I described the use of microfilm and microfiche to store document collections. As most of you know, the next step in the evolution process was a move to storing documents as images.

This was a huge step in the world of litigation support, and honestly it was long overdue when it finally became adopted as a standard. Like so many advancements, it was ‘looked at’ and ‘talked about’ for years before it became the norm. One of the most significant hurdles was simply cost: while the cost to scan documents to create images wasn’t much different than the costs to photocopy or film, image viewing technology was expensive. Firms did not already have this technology, and corporate clients were not willing to bear the cost. Eventually, however, it caught on. By the late 1980’s more and more litigation teams were building databases with images.

There were other changes happening that helped this along – a couple of which meant using images only made sense:

- The use of computers in general was becoming more widespread. Computers were no longer only used by large companies. Small and mid-sized companies were using them. PCs were introduced to the world so large main-frame computers and mini computers were not the only option. Desktop computers were becoming widespread.

- Because the use of computers was growing, more and more commercial software products were available, including commercial litigation support products. Two of the first popular commercial products were Inmagic and BRS Search.

Because of these changes, technology use in law firms grew. Law firms were buying computers for use by attorneys and paralegals. Law firms started hiring IT staff. Law firms started hiring litigation support professionals and buying litigation support software. In short, law firms were developing internal resources to build and maintain databases. They were creating an infrastructure that could support the use of images.

Including images in litigation support databases caused another shift in the way databases were used: because the documents themselves were immediately available in a database, databases were being used more and more often directly by attorneys. They were no longer a ‘back-office’ function. For many years, it was common for law firms to have ‘walk-up’ litigation support stations, but these ‘walk-up’ stations were often used by attorneys, and eventually it became normal to see a computer on every desk in a law firm.

Tune in next week and we’ll continue discussion of how the litigation world circa 1980 evolved and got to where it is today.

Please let us know if there are eDiscovery topics you’d like to see us cover in eDiscoveryDaily.

Disclaimer: The views represented herein are exclusively the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views held by CloudNine Discovery. eDiscoveryDaily is made available by CloudNine Discovery solely for educational purposes to provide general information about general eDiscovery principles and not to provide specific legal advice applicable to any particular circumstance. eDiscoveryDaily should not be used as a substitute for competent legal advice from a lawyer you have retained and who has agreed to represent you.